This year has

been a learning experience in many ways. I’ve expanded my artistic skills and been

introduced to several new types of software, but I’ve also learnt about how

important it is to manage my own creative process. I’ve had a fairly hands-on

lesson about time management, and what happens when it goes wrong, and I’ve

come out of it with a better understanding of how to approach tasks in future.

A lot of the

time, it was down to my inexperience with a certain program, or underestimating

how long something would take. Obviously, on the other side of that, I can now reflect

on what happened and use the experience to plan better for project I do over

the next year, and even further on.

Last year,

over the summer, I’d intended to learn how to use UDK. I put it off while

working on other project, and as a result the building project during the first

term was the first time I ever used the software. While I did manage to learn

what I needed, I still felt very unsure of what I was doing, and that had a big

impact on my ability to work efficiently. I had exactly the same problem after Christmas

– I’d had no prior experience with Z-brush, and therefore I wasn’t able to

anticipate what would be involved when incorporating it into my workflow.

A lot of the

time, I was simply overwhelmed with the amount of information there was to sift

through. Mike Pickton’s video tutorials were often very helpful, but I still

felt quite lost at times. There are plenty of tutorials out there, but most of

them go into much more detail than I needed for what I was doing, and it was

often difficult to find the small piece of information that I was looking for. I

also tend to have trouble working up the confidence to ask for help when I

really need it.

Therefore, if

I want to get the most out of the projects we’re set next year, then I need to

be better prepared. I’m intending to spend the summer better getting to grips

with both Z-brush and UDK. I want to work through some of the more extensive online

tutorials that I didn’t have time to go through when I had a deadline.

I also want

to get more confident at using Photoshop for digital painting. I’ve found

myself using pen and paper much more this year, simply because I find it so

much easier, and I’d like to be able to produce digital sketches and thumbnails

with the same level of confidence.

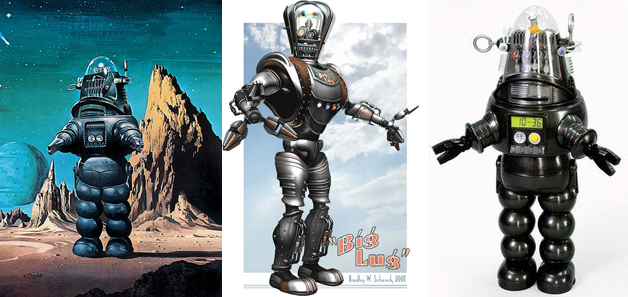

One thing that’s

surprised me this year is how much I enjoy character design. I wasn’t much

interested in it previously; I was much more interested in environments and

buildings. However, despite all the problems and frustration I had with the

Mortal Engines character I very much enjoyed the project, and I’d like to

follow through and improve on the skills I picked up.

I have a tendency

to be a perfectionist and to obsess over detail, and from what I’ve experienced,

that works much better for characters than for environments. I also enjoy drawing people much more than

environments. At this point, I’m strongly leaning towards doing a

character-based project for next year’s FMP.

Next year, I

want to make more of an effort to keep on top of my work, not just to reduce

stress but so I can make better use of the formative feedback sessions. This

does mean I need to be a lot stricter with myself about deadlines and how I use

my time, and also possibly be less overambitious. I am terrible at estimating

how much time a given task will take, and as a rule of thumb I should probably always

allow twice as much time as I think a task will take. That way, if I do finish

a task to schedule then it just means I have time to improve on it further. When

I do come across problems, I need to address them sooner, instead of just

hoping they will solve themselves and letting the work build up.

I feel that I’ve

gotten somewhat better over the last part of this year, especially with the

group project where I managed to keep on top of the work quite well. I’m much

more aware of the need to manage my time, and more recently have had more

success sticking to a schedule I set myself. I’ll try and continue this over

the summer, to stay in practice and just to make sure I spend the time

efficiently.

Ultimately,

universities are for self- development, not just learning set skills, but

finding out how to improve on what skills you have, and to build on what you already

know and enjoy.